This page and the next tell the story of Jean Baptiste Janis, who fought for the Americans against the British in the Battle of Vincennes.

The AuBuchon family tree runs from my grandmother and grandfather back through many generations, some lines extending back to France in the 1600's. The tree provides an occasional place name or date, but there is almost no detail about any of these people. One exception, however, concerns Jean Baptiste Janis, who, it says, "fought with the Americans at the Battle of Vincennes."

I found this line too tantalizing to resist. My research began on the Internet, eventually extending to inter-library loan requests in New Jersey for out-of-print books about Illinois and Arkansas. Although the research continues—there are a few gaps I would like to fill in—on these pages you'll find what I've learned so far, which includes:

- Some detail on the Janis line of the family—and indeed, on all the French-speaking Creoles in the Illinois Country—just before and just after the American Revolution.

- A brief history of the Battle of Vincennes, which unfortunately does not provide any information about Jean Baptiste specifically.

- The U.S. Senate version of a bill that would have given Jean Baptiste $10 per month in return for his service at Vincennes.

- The full text of a speech in the U.S. House of Representatives in support of the House version of the same bill, which does its best to turn Jean Baptiste's feats into the stuff of American legend.

- The result of the U.S. Congress's decision whether or not to turn the bill into law.

There's a lot more here than I originally intended to write, so feel free to use the page contents at the side to skip to whatever you find most interesting. Following the style of a good newspaper article, I've put the most essential information near the top, in the next section immediately below.

In His Own Words (Nearly)

It's not a war journal or a letter to a friend, but, after much digging, I have found what comes close to a description of Jean Baptiste's revolutionary war experience in his own words.

Some Background

First let me briefly put it in historical context. Jean Baptiste Janis was born in 1759 in Kaskaskia, a small town on the Mississippi River in present-day Illinois. At the time, this was part of New France, a vast if vaguely-defined region covering much of what today is the eastern part of Canada, the American midwest and the area around New Orleans. His parents had migrated there from Quebec or Montreal, and Jean Baptiste grew up amongst people who identified themselves as Creoles—French citizens born in the New World.

The year of Jean Baptiste's birth marked the mid-point in the Seven Years War between France and England, the North American theater of which is called the French and Indian War, pitting the French with their Indian allies against the English colonists. The war ended in 1763, and France lost, big-time. They ceded to England all of their territory east of the Mississippi, and to Spain all of their territory to the west. (Wikipedia has an excellent map showing the consequences of the war.)

This left Jean Baptiste and his French compatriots under British rule. Many Creoles crossed the river for Ste. Geneviève, which had been founded in 1740. Those who remained in the Illinois Country liked neither the British nor the English colonists on the east coast, but, after the American Revolution began, if forced to take one side over the other, they generally chose that of the Americans. Their Indian allies, on the other hand, tended to side with the British.

In 1778, in the middle of the war, Jean Baptiste turned 19 and was still living in Kaskaskia. One morning the residents woke up to find the town had been taken over by the Americans in the middle of the night. Their leader was the charismatic George Rogers Clark, in the Virginia militia. For reasons unknown—but probably not simply because they were inspired by the principles laid out in the Declaration of Independence—about a hundred Frenchmen, including young Jean Baptiste Janis, decided to enlist in Clark's company. He had a daring plan to surprise the British at Vincennes, 180 miles to the east. In February of 1779, his mix of French settlers and Virginia backwoodsmen set off. The getting-there was very difficult, but Clark's men took Vincennes without losing a single soldier.

Four years later, the Americans won the war and began pouring into Ohio, Indiana and Illinois. The victors brought with them scorn for the land practices—and, more generally the way of life—of the French settlers who had come before them. In response, and like many other Creoles, Jean Baptiste took his family across the river to Ste. Geneviève, still under Spanish control. In 1800, they briefly enjoyed French rule for a time, until the Louisiana Purchase of 1803 once again put the French under American dominion. And once again they found themselves overrun by Americans, but this time with no place to flee. Missouri became a state in 1821.

What was a period of wealth and expansion for the Americans was, of course, a time of devastation for the Native Americans. While the French Creoles did not perish, their culture did, and while some Creoles thrived, many lost their land in the transfer of Missouri from Spanish to American control.

Jean Baptiste was one of these. In 1833 he was 74 years old and impoverished. At that time, the American government was becoming increasingly conscious of the debt it owed to the soldiers who had fought, unpaid, in its war for independence. More and more veterans and their widows were beginning to receive compensation. Jean Baptiste set about taking the steps necessary to obtain the same for himself, which included the paperwork verifying and attesting to his contribution to the American cause. In 1833 he made a formal petition to the United States Congress.

The Petition

What follows comes verbatim from Southern Campaigns' Revolutionary War Pension Statements & Rosters, a website which provides transcriptions of archival material related to the Revolutionary War.

To the Senate & House of Representatives of the United States in Congress Assembled

Oppressed with age and infirmity and in want of many comforts of life the undersigned begs leave respectfully to present this petition to the Congress of the United States.

Your petitioner states that in the summer of 1778, Kaskaskia was taken by Colonel George Rogers Clarke [George Rogers Clark] of the Virginia line, he was then young and ardent and although a stranger to the laws, customs & language and institutions of the Americans, he became animated in support of the great cause for which they were struggling, and on many occasions manifested his devotion in a way as he believes to secure the entire confidence of the Army and of its officers.

Your petitioner further states, that in the course of the summer a company of volunteers was organized composed of the French inhabitants on a call from Colonel Clarke. In this company your petitioner was appointed an Ensign by his Excellency Patrick Henry then Governor of the State of Virginia which commission is exhibited with this petition. Your Petitioner states that this Company was required to be ready for active service on a minutes notice, that many of its members were employed as hunters and spies then required when necessary to perform Garrison duty.

Your Petitioner further states that the term of time for which Colonel Clarke's men were enlisted having expired, many of them returned to their homes, which had the effect of weakening his force to an alarming extent and rendered his situation in that vast wilderness critical in the extreme. About this period Colonel Hamilton Commandant at Vincennes commenced assembling an army of British & Indians with the avowed the purpose of not only expelling his enemies from Kaskaskia and Cahokia but to drive the Americans East of the mountains. At this juncture Colonel Clarke determined on his daring expedition against Vincennes. Your petitioner further states that without the aid of the French inhabitants of Kaskaskia and Cahokia the power of the Americans was unequal to the task of capturing Vincennes, at that time the center of British influence. But in this emergency Colonel Clarke called upon the French to take part in the expedition as volunteers, which call was promptly responded to. Two Companies were accordingly raised, and equipped at their own expense, one under the command of Captain Charleville of Kaskaskia, the other under Captain McCarty of Cahokia. Your petitioner acted as Ensign in the company of Charleville. These two companies added to the Americans made a combined force of 170 men. With this small array Colonel Clarke marched in the month of February 1779 and after swimming rivers and creeks, wading for miles through waters amid snow & ice, suffering the extremes of hunger and fatigue, they surmounted every obstacle and towards the close of the month, arrived before Vincennes, where the flag of the United States was planted by the hand of your petitioner within gun shot of its walls. Your petitioner further states that after a few days siege, conducted with consummate skill by Colonel Clarke this important place fell and with it forever the British power in the valley of the Mississippi. Your petitioner further states that during the whole period the American troops held possession of Kaskaskia & Cahokia they were quartered on the inhabitants or sustained by requisitions. Your petitioner's friends and relations made advances for which compensation to this day has never been made. For these services and sacrifices, your petitioner prays that his name, during his few remaining days be placed on the Pension Roll, or such other provision made for him as the justice of his case would seem to demand. Your petitioner begs leave further to say that in the year of 1796 he being then a married man and the father of 8 children removed from Kaskaskia to St. Genevieve in the Spanish province of Louisiana with the intention of acquiring lands for his family under the liberal policy pursued by the Spanish Government in making donations to settlers. He made application for a conception of 8000 acres which was granted by the St. Governor. On the transfer of Louisiana to the Americans a law was passed by Congress requiring that all concessions should be registered by a certain day. Your petitioner unacquainted with the English language never heard of this law and his claim not being recorded in accordance with its provisions was consequently lost to him. Thus your petitioner served this country in his youth without compensation and in his old age finds himself deprived by law of that property which was generously bestowed on him by another Government.

(To view his signature click on the link above or go to Three Signatures below, where it is compared to two other of his signatures.)

Even 25 years ago historians believed that Jean Baptiste Janis' request for compensation was denied (see for example Lankford). But the transcription above, at its end, clearly states that he received a pension of $120 per year back-dated to 1831. Moreover, as explained below, I have independently verified that Congress approved his request. It therefore seems that the recently-begun process of making historical records available on the Internet has given me the chance to rewrite history.

That's the end of my abridged history of Jean Baptiste Janis, veteran of the Revolutionary War. What follows are the details, where practically everything described above receives considerable elaboration, starting with how to pronounce our hero's last name.

A Little French

The Janis line of our family goes back to France. Now, usually I have no objection to anglicizing a French word or name, but the difference between the English and French versions of this name is so great that I think in this case it's worth a little time and energy. The name is not pronounced like the Janis in Janis Joplin. Rather, it sounds like this. (If you have trouble with the page linked to, see the Using the "How to Pronounce" Website page.) In case the link is bad or you don't have sound on your computer, let me give you the sounds.

- The 'j' is pronounced like the 's' in the word Asia.

- The 'a' is pronounced something like the 'a' in Ma.

- The 'n' should be no problem.

- The 'i' is pronounced like the double-'e' in feet.

- The final 's' is silent.

A Little Geography

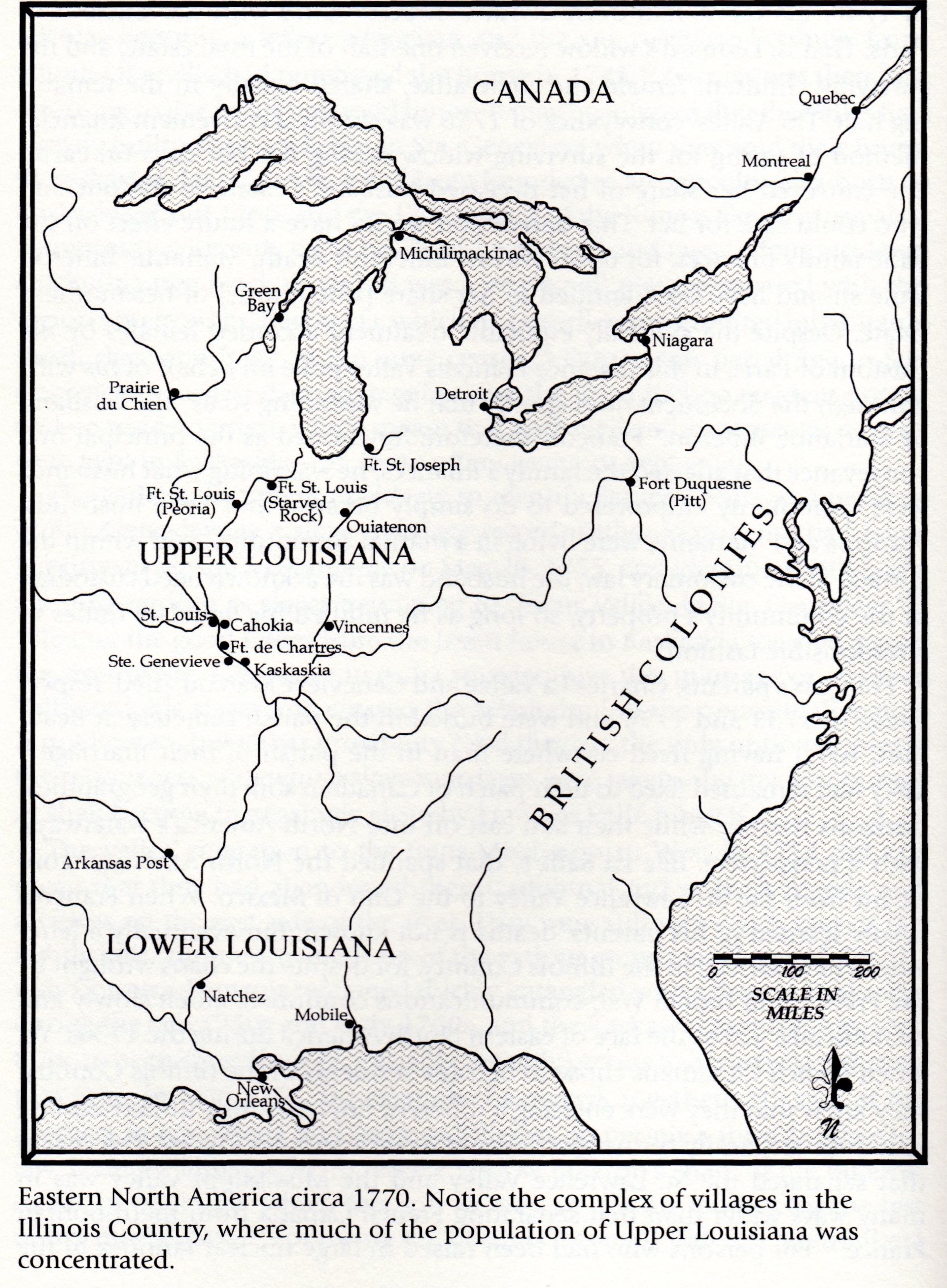

This map, from Carl J. Ekberg, François Vallé and His World (a biography of a patriarch of another branch of the family tree), shows all the important towns in this discussion: Ste. Geneviève and Kaskaskia, on opposite sides of the Mississippi, as well as Vincennes, 180 miles to the east. Fort Duquesne, later Fort Pitt, and Pittsburgh after that, plays a small role as the starting point for George Rogers Clark on his journey down the Ohio to Kaskaskia. Way up in the northeast sit Montreal and Quebec, the stepping stones my ancestors used on their way to Upper Louisiana, aka the Illinois Country.

The Name "Jean Baptiste"

Jean Baptiste is the French version of John the Baptist. In her book, Kaskaskia Under the French Regime, Natalia Meree Belting, while discussing some of the festivals the French Creole celebrated, mentions just how common this given name was.

The fête day of St. Jean Baptiste, patron saint of Canada and most popular patron in Illinois, marked midsummer, and was celebrated with ancient pagan customs. On the evening of June 24, the elders of the village hunted for sacred herbs to provide future remedies, and the children went from door to door begging for fagots to burn. At nightfall the wood was heaped in a great pile, and the oldest habitant or perhaps the curé, threw on a flaming brand. In the church there were special services the next day and another procession. Those men and boys who had been named for the saint, and there was one Jean Baptiste in practically every Kaskaskia family, kept their birthday anniversaries then as was the custom in Catholic countries. (p. 70)

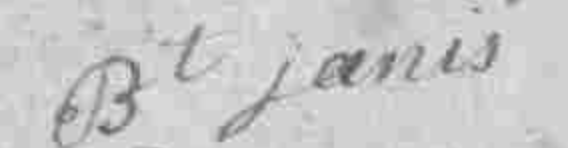

While digging into old church records for The Janis Line, Pt. 1, I soon learned that the name Jean Baptiste was so common it is frequently abbreviated as "Jean Bte." Our particular Jean Baptiste sometimes signed his name as "Bt Janis," or "Bte. Janis," dropping the first name entirely. We'll see that a little bit later on this page.

The Janis Family

It's six generations back from my mother, Corinne AuBuchon Kurlandski, to Jean Baptiste Janis, the hero of this 18th Century tale set in the heart of North America. But our family tree for the Janis line goes back even further, to the Champagne region of France in the mid-1600s. All this and more is explored on the The Janis Line, Pt. 1 page.

Here's the part of our tree for Jean Baptiste Janis going back to his grandparents, François Janis and Simone Brousseau, born in France and married in Trois Rivières, Quebec in 1704.

├── Jean Janis == Marie Paquet ├── François Janis (b. 1676) == Simone Brousseau (1684-1746) ├── Nicolas Janis (1720-1804) == Marie Louise Thaumur (1737-1791) ├── Jean Baptiste Janis (1759-1836)

So according to the family tree, our hero, Jean Baptiste Janis, (starting from the bottom) had a father whose name was Nicolas Janis, and a grandfather named François Janis, and a great-grandfather named Jean Janis. But my most valuable source on the Battle of Vincennes casts some doubt on this information with regard to his grandparents, and therefore with regard to his great-grandparents as well. (That's why I call this site Adventures in Genealogy. It's never easy going for long. Usually it seems as difficult as Jean Baptiste's trek through the Indiana wilderness to Vincennes. Which we will get to eventually, I promise.) These questions are explored in the The Matter of Two Nicolases section of the "Janis Line" page.

The valuable source referred to above is "Almost 'Illinark': The French Presence in Northeast Arkansas," by George E. Lankford. For the most part, we will follow him on our journey to Vincennes. Here he is discussing Nicolas Janis, born in 1720, the father of Jean Baptiste Janis:

Nicholas Janis was an important man both in French Illinois and in his family, as his consistent signature suggests; it is always just “Janis,” without further specification. [... He] appeared as a young man in Kaskaskia and Sainte Geneviève around the middle of the century. His first appearances in the records were in 1751, when he sold a house and land in Kaskaskia for four hundred livres, suggesting he had already been there long enough to purchase or build that property. That same year he married Marie Louise Taumur, daughter of Jean Baptiste Taumur dit La Source and Marie François Rivard, who had long been members of the Kaskaskia community. Ekberg thinks that he first settled in the fledgling village of Sainte Geneviève for a few years, before selling his property there and moving to the older Kaskaskia. What is clear is that he quickly became one of the pillars of French Illinois, established at the principal village on the east side of the Mississippi River.

Let's follow Lankford's reference above to Ekberg's Colonial Ste. Genevieve: An Adventure on the Mississippi Frontier. Ekberg writes:

Also of interest for the early history of the Old Town are two men, Janis and Chaponga, who were cited in Rivard's grant as adjoining property owners and must therefore have owned land in Ste. Genevieve's Big Field before Rivard requested his grant. It seems certain that this Janis was Nicolas Janis, who married a sister of the Lasource brothers, Marie-Louise, in April 1751, and who probably moved to Ste. Genevieve with his new bride. Logically, Janis and his wife should have appeared in the town's census for 1752, but they did not. (p. 35-36)

Perhaps he did not appear in the census because by that time he and Marie-Louise had moved across the river to Kaskaskia? In any case, Nicholas and Marie Louise had six or seven children. Lankford continues:

They apparently grew prosperous at their endeavors, for when the French and Indian War came to an end in 1763, they became part of the British empire rather than fleeing to another area of the world remaining under French domination. They were well aware of the fact that Arkansas Post, Ste. Geneviève, and the young St. Louis had become Spanish, but they seemed content to be British in Kaskaskia. C. W. Alvord described them this way: “Among the gentry, which was a rather elastic term, were also many well-to-do men, who had risen to prominence in the Illinois or else possessed some patrimony, before migrating to the West, which they increased by trade.... These members of the gentry lived far more elegantly than the American backwoodsman and were their superiors in culture. Their houses were commodious and their life was made easy for themselves and families by a large retinue of slaves.” A hint of the quality of life in Kaskaskia comes as a historical detail: when Nicholas Janis’s daughter Félicité married Vital Bauvais in 1776, one of the gowns in her wedding trousseau was made from material which had come from France that same year.

Life in British Illinois was not without its problems, though, and when George Rogers Clark arrived to conquer the Illinois on behalf of the new United States in 1778, he found that no battle was necessary, for the Kaskaskia French received them with enthusiasm and embraced the end of English control. They fed Clark’s army and even provided volunteers for the winter march to capture Vincennes, a brief campaign whose victory made a hero of young Jean Baptiste Janis. (p. 97)

"Young" is right: having been born in 1759, Jean Baptiste was just 19 or so when he joined Clark's troops to head for battle. The French and Indian War had ended when he was just four, so it is possible that he had never fired a gun at another person before—especially if his life had been as easy as Lankford describes. Perhaps Jean Baptiste recognized this in himself, his lack of experience in things considered manly, and perhaps this was what prompted him to volunteer.

The Battle of Vincennes

Lead-Up

Present-day Illinois and Indiana—the "Illinois Country," named after the Illinois Indians—were originally settled by the French. After the French and Indian War, the British gained control of this area and the Spanish soon won the lands west of the Mississippi. There were only about 2,000-5,000 French settlers living in the Illinois Country, largely concentrated in Kaskaskia, Prairie du Rocher, Cahokia and Vincennes. The French did not tend to live in isolated farms scattered far from one another.

Then the American Revolution began. While the famous battles—the stuff we learn about in school—were taking place along the East Coast, there was also considerable engagement in the interior of the continent.

The American Indians were for the most part aligned with the British, who discouraged the colonists from encroaching on Indian land. The French settlers in the Illinois Country would have wanted to remain neutral, no doubt preferring to be left alone. But when the Americans and British engaged in Upper Louisiana, the French would often be forced to choose a side. In these cases they generally sided with the Americans, perhaps because of their historical antipathy toward the English. Once news of France's official support of the Americans arrived, their sentiments tended to favor the Americans even more.

In late 1778 a force of about 90 British regulars and 200 Native Americans arrived at the town of Vincennes, located on the Wabash River between what would become the states of Illinois and Indiana. The British commander, Lieutenant Governor Henry Hamilton, immediately set to work improving the fortifications of the stockade next to the town, at the time called Fort Sackville. The French townspeople were forced to swear an oath of allegiance, and from the men among them Hamilton formed a militia of about 250. Some of these men would serve the British well. However, Hamilton would have been keenly aware of the French militia's weak loyalty to the British crown.

(Drawing from Indiana Historical Bureau.)

Over in American-occupied Kaskaskia, George Rogers Clark recognized that, come spring, Hamilton's forces would regroup and begin operations against Kaskaskia and any other American-held towns in the Illinois Country. Outnumbered, his men would have little hope against them. Clark therefore conceived of a plan to take Vincennes in a surprise winter attack.

Clark had no more than 200 men, and was losing many of them because their enlistments were expiring. He managed to persuade about half to extend their enlistment eight months, and began recruiting French settlers into his small army.

Our hero, Jean Baptiste Janis, was one of these. Back then he and his compatriots would have been referred to as Creoles, meaning that, though they spoke French and were of French ancestry, they were born in the New World. We know nothing of these Creoles' motivation for joining Clark. Alberts gives us a hint of the weakness of their tenuous support for the American cause, writing of Clark's position in Kaskaskia, "He had fewer than 200 men, nearly half of them French volunteers of unproved dependability, and he was cut off from communication and probably from reinforcement from the east." (p. 28)

While we don't know the general reasons why some of the French volunteered to fight for Clark, let's spend a little time speculating about Jean Baptiste's motives. As documented above in the quotations from Lankford, as well as in The Nicolas Side section of the Janis Line page, Jean Baptiste's father had come to Kaskaskia as a young man with nothing, married in 1751, and by the time Clark appeared on the scene in 1779 was captain of the militia and an elected magistrate—and no doubt enjoying an economic situation commensurate with his social standing. Turning 19 in 1779, Jean Baptiste possibly realized he had a very big pair of shoes to fill. So when the chance to make a name for himself came, he seized it.

The Battle

On February 5th, 1779, Clark's march on Vincennes began. Their chief obstacle was not the cold but miles and miles of flooded plain. A good portion of the journey involved wading rather than hiking. The Civil War Trust's map of the last nine miles shows just how much of the end of the trek lay under water. At places it was up to their shoulders.

By the time Clark and his men neared Vincennes on the 20th, they were running short of food, and the most exhausted among them had to be shuttled from one dry patch to another by canoe. Wikipedia quotes the journal of one of the captains, describing the men as "very quiet but hungry; some almost in despair; many of the creole volunteers talking of returning." He added, "Those that were weak and famished from so much fatigue went in the canoes." Alberts describes them as scrounging for hickory nuts and pecans on the ground, as well as roasting a fox for nourishment (p. 44).

Clark and his men entered the town of Vincennes on February 23rd. Inside the fort, the British were unaware of their presence. One near-disastrous result of Clark's risky decision to attack by land lay in the fact that, after wading through water, nearly all of his small army's gunpowder had been ruined. Fortunately for him, François Busseron—a pro-American fur trader serving in Hamilton's French militia—was able to lead the American commander to the place where he had hidden Vincennes' gunpowder three months earlier. Busseron then "hurried to the fort to report for duty, apologizing for having been unavoidably delayed" (Alberts, p. 46).

We know that Busseron did not report the Americans' presence in the village to the British inside the fort. What we don't know is whether he whispered a warning to his French compatriots also serving in the militia. In any case, the Americans opened fire at around sunset, taking Hamilton and his men by surprise. The British tried to respond with cannon, but the Americans shot at their gunmen through the open portholes. Moreover, since the Americans had taken cover behind the houses near the fort, the British commander feared that destroying the French dwellings would only turn the residents against him, as well as weaken the resolve of the French militia fighting from inside the fort on behalf of the British.

At some point during the night a Piankeshaw chief named Tobacco's Son arrived with about 100 warriors. Alberts refers to him as Clark's "old friend" (p. 47), but nowhere does he explain how, or for how long, the two knew each other. Tobacco's Son offered to assist in the siege of the fort, but Clark declined, fearing that his men might not be able to distinguish them from the Indians fighting on the British side.

The next morning Clark and Lieutenant Governor Hamilton began negotiating terms of surrender. During these negotiations, the Americans' chief advantage lay in Hamilton's false impression of the size of Clark's forces. At this point, circumstances gave Clark an opportunity to cause the Indians defending the fort to have second thoughts about their support of the British.

That is, perhaps, the most generous way of describing what Clark did. Wikipedia calls it "the most controversial incident in Clark's career." The Civil War Trust's page almost apologetically introduces the event as "one of the most controversial and brutal episodes of the frontier wars."

Since the shooting had stopped while negotiations were taking place, and since the British flag was still raised over the fort, a party of Indians and the British-organized French militia entered the town unaware of the American siege. Clark's men captured them. The French were released, but the four Indians were sat in full view of the fort and tomahawked to death. They were then scalped and their bodies thrown into the river. (See George Rogers Clark note below.)

Historians seem to disagree whether this weakened or strengthened the resolve of the Indians inside the fort. In any case, Hamilton and Clark finally agreed on the terms of surrender, and the American flag was raised over Fort Sackville at 10 a.m. on the morning of the 25th.

The same website cited above, in the "Aftermath" section, lists 20 casualties--four American (American/French, no doubt) and 16 British. There is no mention of the Native Americans whom Clark ordered his troops to tomahawk and scalp, or any other Native Americans.

After the Revolution

Historians of war may disagree about the impact the Battle of Vincennes had on the American Revolution, but there is no dispute over who won the war. The British were forced to withdraw from the thirteen colonies as well as Upper Louisiana, while maintaining control of what would become Canada. The Americans would soon cross the Appalachians in increasing numbers, settling in the Illinois Country, which technically belonged to Virginia until the former colony ceded it to the United States. Eventually the separate territories of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan and Wisconsin would be formed and join the United States.

These were not happy times for the Native Americans living there. Take for example the Piankeshaw, whose chief Tobacco's Son offered to assist George Rogers Clark in his attack on Fort Sackville: prior to the American revolution, this tribe was known to be less hostile to settlers than others. "The Piankeshaw are usually regarded as being 'friendly' towards European settlers. They intermarried with French traders and were treated as equals by residents of New France in the Illinois Country" ("Piankeshaw" in Wikipedia). In the late 1700's their population declined, hurt by warfare and economic circumstances. A hard winter followed by a drought in 1781 was devastating, and the increasing settlement by the Americans after the Revolution eventually drove them either out of the Illinois Country or into tribes resisting American encroachment. In 1818 they were finally forced to sign a treaty ceding much of their land to the United States. The few remaining tribes people eventually became part of the Peoria tribe of Oklahoma.

And what of the French Creoles living in Upper Louisiana?

Before the war had even ended, François Busseron—the French fur trader who had supplied Clark with the hidden gunpowder—was perhaps having regrets about his support for the American cause.

By 1781, the Canadian residents of Vincennes had become frustrated with the Virginia government, depreciated US currency, and the Virginia militias that used or took their property without proper compensation. The leading citizens of Vincennes, including François Busseron, signed a letter of grievances to the governor of Virginia. Over the course of the American Revolution, Busseron extended up to $12,000 credit to Clark. None of this was ever repaid to him. He and all but one of his children died in poverty. ("François Riday Busseron" in Wikipedia)

Busseron died at the age of 43, two years after the U.S. Constitution was ratified. But the stability which the new federal government provided did not significantly improve the lives of those living in the Illinois Country.

American settlers began to move into Vincennes—70 families by 1786, most of them squatters occupying land near the fort. With them they brought an independent spirit, initiative, advanced technology, and some small amount of capital with which to begin to build and develop. But they also brought the problems inevitable to newcomers in a changing economy and in the clash of dissimilar cultures. They distrusted and detested the Indians, and with no one to regulate the Indian trade, they debauched them with their corn whiskey. They quarreled with the French habitants, whom they considered lazy, whose ancient customs they scorned, and whose local government they mocked. They corrupted the economy with worthless Continental currency and claimed ownership of more and more land, some of it devoted to communal use, much of it occupied by the French for generations. Fort Patrick Henry (old Fort Sackville) was stripped for building materials and left in ruins. Vincennes was in a state of virtual anarchy, almost in a reign of terror. (Alberts, p. 57)

It sounds as though the Americans were intent on making the land their own, at any cost, and they justified their ill-treatment of the French by despising their way of life. This is not unlike the way they treated the Native Americans.

Ekberg has a very interesting article which explains the communal nature of the Creole settlers' agricultural system, and he argues persuasively that it led to a mutually dependent, much less violent society than the system which American settlers would practice as they migrated into the Illinois Country. The communal nature of the Creole system required that farmers work together. It is easy to imagine how quickly the system would break down with the arrival of significant numbers of people who would refuse to participate.

The Janis Family

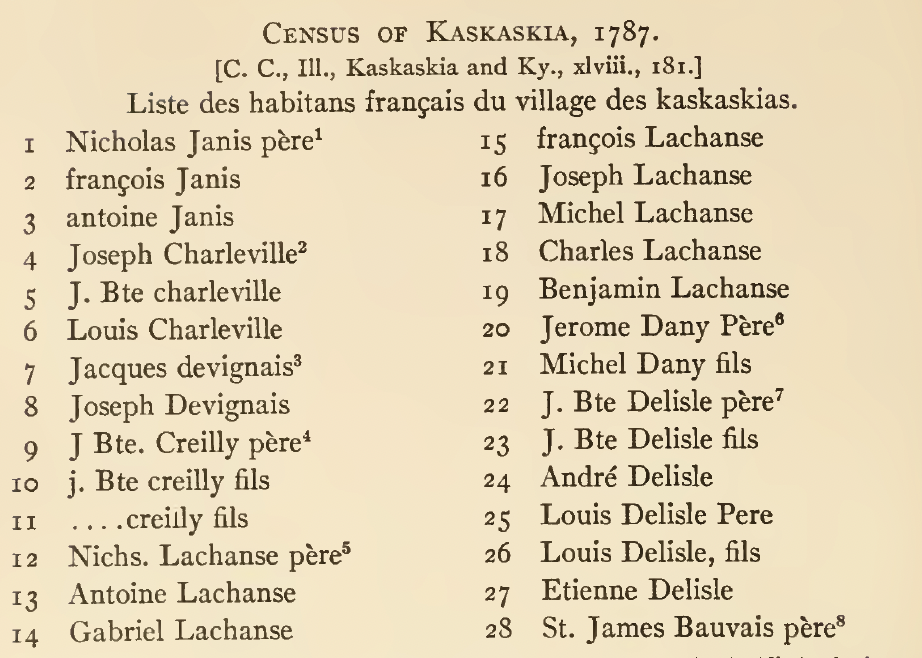

The 1987 Kaskaskia Census (see Notes on Alvord's Kaskaskia Records (1778-1790)) records Nicolas Janis and two of his sons as Kaskaskia residents, but there is no mention of Jean Baptiste. To find Jean Bte., you have to look in the Prairie du Rocher census of the same year, where you'll find him with his two sons Jean Baptiste and Antre (sic: André maybe?). His wife was from Prairie du Rocher; it seems reasonable to think that they decided to live there after they married so she could be close to her family. Perhaps Jean Baptiste was happy to acquiesce, if only to get out of his father's shadow. Alvord's reprint of the Prairie du Rocher census has this footnote concerning Jean Baptiste: He was the son of Nicolas Janis (see ante, p. i8, n. 4), and was born in 1759. He was appointed ensign in the Illinois regiment by Clark and served during the Vincennes campaign. His services were particularly praised by Clark. His wife was Rene Julia Barbau, by whom he had eight children. He finally moved to Ste.Genevieve, Mo. Houck, Hist, oj Missouri, 1., 354, n. 43. At this point we can return to Lankford's narration of the Janis family. Like Busseron in Vincennes, Jean Baptiste's father, Nicolas, had served as a captain in the British militia in Kaskaskia. His duties there ended, of course, when George Rogers Clark took over the town. In 1779, the French citizenry made him a judge. Since the land was now claimed by Virginia, his authority as a justice—and, indeed, the power of the French to rule themselves— was considerably weakened. It was not clear who was in charge and a number of different English-speaking strangers arrived in the Illinois Country, each claiming to be the legitimate representative of the Virginia government. There began a major French exodus to the Spanish, the western, side of the Mississippi, to the point that the Illinois Country they left behind could be described as "depopulated." All of the major Creole families seem to have disappeared from the official records there—the baptismal and marriage certificates, for example—except for the name of "Janis." While his neighbors crossed the river, Nicholas Janis held out in Kaskaskia through these years; the Janis family left in groups for Spanish territory in the late 1780s, but Nicholas did not leave until the end of the decade. Jean Baptiste and François and their families went from Prairie du Rocher to Sainte Geneviève. [...] It appears that Nicholas the patriarch did not move to Sainte Geneviève until 1790 or 1791. (p. 99) Ekberg, in Colonial Ste. Genevieve, says that Nicolas moved across the river in 1788, and at the time had 19 slaves, an indication that he was "well-to-do" (p. 428). What about Jean Baptiste? In his letter to Congress, quoted above, Jean Baptiste wrote that he received 8,000 acres from the Spanish government after he moved to the Ste. Geneviève side of the Mississippi, and that he lost it all on the transfer of the Louisiana Territory to the Americans, leaving him, as he says at the very beginning, "oppressed with age and infirmity and in want of many comforts of life." He doesn't describe with any specificity what happened, but attributes it to his own weak English: "your petitioner unacquainted with the English language never heard of this law." Lankford doesn't fill in the details regarding Jean Baptiste in particular, but he provides some detail regarding the general case. As long as the settlers remained under the Spanish flag, possession and improvement of the land was sufficient title, but the transition to U.S. territorial status in the opening decades of the nineteenth century forced the regularization of land titles. The Board of Land Commissioners found themselves having to determine "legitimacy" for prior land ownership. Their task was complicated by land fraud—and the belated attempts by some of the Spanish commandants to give settlers legal grants before the Americans took over. The board's response was to set strict standards which had to be met in order to show the legitimacy of a claim, including proof that the claimants were actually living on the land prior to December 1803, or even earlier, and that they were farming significant acreage. Both the standards and the process of providing proof were difficult for the French, and they saw little chance of success. Moreover, there may have been some anti-Gallic bias involved, for the board refused to confirm the joint ownership of the commons in the French towns, and thus voted against the European settlement pattern itself. (p. 109) So the country for whose existence John Baptiste had gone to war would in the end take away his land and therefore his means of sustenance. How he and his grown children fed, clothed and sheltered themselves we do not know. But his father Nicolas Janis died in 1808, and Jean Baptiste watched his son Jean Baptiste fils die before him in 1830 at the age of 56. It was just then, in the early 30's, that the U.S. Government began the task of compensating its revolutionary soldiers for their unpaid service. A law was passed requiring proof of a minimum of six months of service in order to qualify for a pension. It appears that Jean Baptiste's proof of service, at least for a time, got lost in government bureaucracy, for, on the same web page as the petition to Congress quoted above, you will find the transcript of a sworn affidavit wherein Jean Baptiste attests to a number of facts, including: His effort to secure himself a belated pension had hit an impasse. But then the United States Congress came to his rescue. Click on the link at the bottom of this page for our next exciting episode. I have three different signatures belonging to Jean Baptiste, written in three significantly different circumstances. The first is from his 1781 marriage contract, documented in these pages under Marriage of Jean Baptiste Janis. He was about 24 at the time. The second and third come from documents he signed while trying to get his pension some 50 years later, and can be found at Southern Campaigns' Revolutionary War Pension Statements & Rosters. They both appear to come from records dated 1833, but in the first of this pair he signs himself as the French or Creole "Bte Janis," even going so far as to abbreviate the middle name, as the French at that time and place were wont to do. The third signature, also from 1833, is much more anglicized—"John Baptiste Janis." Moreover, it strikes me as coming from a different hand altogether: just compare the three capital "B"s. But even you wouldn't go so far as that, it appears to me that he and whoever was helping him were making a last-ditch effort to appeal to the English-speaking government back East, a government completely foreign to him but all-powerful in deciding his fate. So, I think, he tried, or was persuaded to try, to appear as American as he possibly could. This last signature was copied from the end of The Petition Jean Baptiste sent to Congress, which is quoted above. I think I can make out part of what follows his name: "(illegible) of Missouri." The last word is hard because the handwriting mixes two different "s"s—first the old-fashioned long "s," then the one similar to the modern "s." (referenced in The Battle) I wrote this page in 2015. I write this note in 2021. During these intervening years, a statue of Clark has been one of four sculptures removed from Charlottesville, Virginia amidst considerable controversy. It is interesting that, in my somewhat cursory googling, I have not found the atrocity he committed at Vincennes offered as a justification for the statue's removal. (See, for example, UVA and the History of Race: The George Rogers Clark Statue and Native Americans | UVA Today.) I think there should be a national museum dedicated to banished historical artwork. Perhaps as part of the Smithsonian Institute. Each piece would have a couple of paragraphs of text and audio describing its history as well as the person or historical event it's commemorating—ending with the story behind its banishment. An analysis from an art history perspective would also be interesting.... I would go to such a museum.

Three Signatures

Notes

George Rogers Clark