On this page I share what I've learned about my great-grandfather Ludwig Kurlandsky, also known as Louis R. Kurlandski and the husband of my great-grandmother, Sophia M. Kurlandski, née Sophia Preis. For how I came upon this information, see On the Trail of Sophia & Louis.

The Ellis Island Records

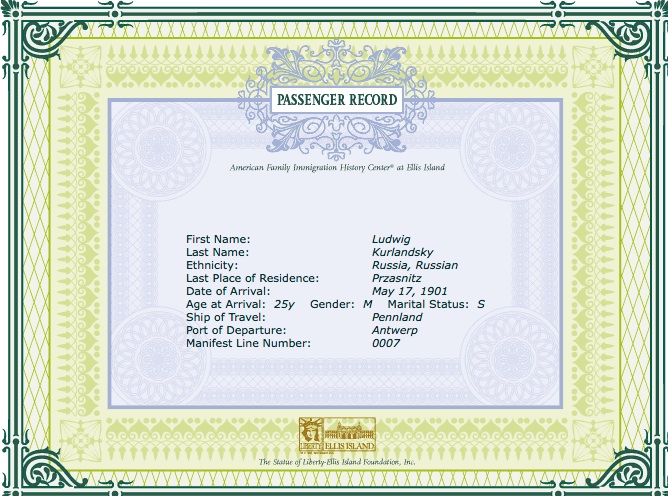

The Ellis Island records show Ludwig as having entered the country in 1901. Here's a copy of the passenger record which the Ellis Island Foundation would like to sell me.

Przasnysz

Though the certificate says he was Russian, it also says he came from Przasnitz, which I assume is more properly spelled "Przasnysz", and which is both a region and a town in present-day Poland. On the one hand, this makes sense—at that time Poland did not exist as an official country. On the other hand, for the 1910 U.S. census, he identified himself as immigrating from Germany.... So which was it—Russia or Germany?

The following map, showing the location of Przasnysz in Poland today, was lifted from the Wikipedia entry.

But that's today. What about in 1900? According to the site JewishGen, "Przasnysz History", Przasnysz became part of the Russian Empire after the Congress of Poland in 1815. And as far as I can tell nothing much seems to have happened there until the First World War. Perhaps that's why Ludwig and his brother felt compelled to pull up roots and cross the Atlantic—they belonged to a nation without a country.

I have searched extensively online for a map of where Przasnysz sat in Eastern Europe in 1900, and have not been able to find one. The closest I've come is the following, from Euratlas Periodis Web - Map of Europe in Year 1900.

A comparison between this map and the preceding (of current-day Poland), suggests to me that Przasnysz lay just south of the German-Russian border—in other words, just inside Russia. Perhaps this very proximity is what led Ludwig to identify himself as Russian to the crew of the Pennland, but as German/Polish to the census takers. (For more like this, see Polish Geography below.)

Other Details

When I found the Ellis Island records for Ludwig, I couldn't at first be sure that it was my great-grandfather. But a close look at the ship's manifest reveals some information that removes most of our initial skepticism. Columns 11 through 16 of the manifest tell us his final destination was to meet his brother in St. Louis, and that his brother had paid for his passage. Other information tells us that he was a laborer, he could read and write, and that he was neither crippled nor a polygamist (whew!).

Here's the information I've gleaned from the manifest, as well as Ludwig's part of the manifest.

| Question | Answer | My Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Name in full | Ludwig Kurlandsky | |

| Age | 25 | |

| Sex | M | |

| Married or Single | Single | |

| Calling or Occupation | Laborer | |

| Able to Read/Write | Yes/Yes | This is my reading of the double quotes in these columns. I'm not sure how to interpret the slash in the Read column. |

| Nationality | Russian | |

| Last residence | (illegible) | I can't read the answer, but "Przasnitz" or "Przasnytz" is possible. |

| Seaport for landing in the U.S. | New York | |

| Final destination | St. Louis, Mo (?) | |

| Whether having a ticket to such final destination | Yes | |

| By whom was passage paid | Brother | |

| Whether in possession of money. If so, whether more than $20 and how much if $20 or less | $60 | |

| Whether ever before in the U.S. | No | |

| Whether going to join a relative and if so, what relative (illegible) name and address | brother (illegible) St. Louis | |

| Ever in prison or (illegible) or supervised by charity, if yes, state which | No | |

| Whether a polygamist | No | |

| Whether under contract, (illegible) in the United States | No | |

| Condition of Health, Mental and Physical | Good | |

| Deformed or crippled, nature and cause | No | |

| Pennland manifest containing Ludwig Kurlandsky on line 7 |

As luck would have it, the most interesting information in this manifest is the least legible: the bit about his brother. If any reader would like to have a shot at making out that part of the manifest, be my guest. (For more, see Ludwig's Siblings.)

The Pennland

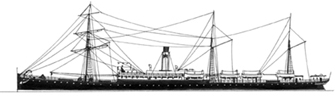

The Ellis Island records show that Ludwig arrived on the Pennland, and they give the following information about the ship.

Built by J. & G. Thomson Limited, Clydebank, Scotland, 1870. 3,760 gross tons; 361 (bp) feet long; 41 feet wide. Compound engine, single screw. Service speed 13 knots. 1,200 passengers (200 first class, 1,000 third class).

Built for Cunard Line, British flag, in 1870 and named Algeria. British service. Sold to Red Star Line, British flag, in 1882 and renamed Pennland. Antwerp-New York service. Scrapped in 1903.

So the ship Great-Grandfather Ludwig took to this country was built in 1870 for the Cunard Line.

Coincidentally, I started a new job in downtown Manhattan just before doing this research in 2014. One of the older buildings at the very bottom of Broadway—overlooking the harbor with its Statue of Liberty and the more-distant Ellis Island, is a building with the words "Cunard Line" ostentatiously engraved just above the door.

When I first noticed the doorway, I thought it had once been the entrance to an old subway line, until one day—doubting that even in its early days the subway system had that much wherewithal—I googled the phrase. It turns out that the Cunard Line was one of the leading operators of passenger ships—some of the company's more famous vessels were the Queen Mary, the Queen Elizabeth and, more historically resonant, the Lusitania.

All of which would be a digression if it were not for the following. Ludwig's ship the Pennland was sold to the Red Star Line almost 20 years before he boarded it, and scrapped just two years later. This probably means it was not much of a ship—certainly not by 1901.

Side note: A second Pennland was built several years later for the Red Star Line. The Wikipedia entry on the Red Star Line describes a Pennland which was sold to the line in 1935, and later served as an allied troop ship.

Antwerp and The Red Star Line

The Red Star Line operated out of Antwerp, Beligium. Unlike the Cunard Line, the company did not survive the depression. The Wikipedia entry for the line has the following (for "Warschau" read "Warsaw").

In the city of Antwerp, the former warehouses of the Red Star Line were recently landmarked and reopened as a museum on September 28, 2013 by the City of Antwerp. The main focus of the museum are the travel stories that could be retrieved through relatives of Red Star Line passengers. In the exhibition the visitor follows the land movers' tracks from the travel agency in Warschau until their arrival in New York. The works of art of the Red Star Line emigrants made by the Antwerp artist Eugeen Van Mieghem (1875-1930) will be exhibited there, next to Red Star Line memorabilia of the collection of Robert Vervoort.

It seems as though parts of the exhibition described above made its way to the U.S. in 2006. A New York Times review of the exhibition by Grace Glueck, entitled "Antwerp = America: Eugeen Van Mieghem and the Emigrants of the Red Star Line" describes the artist's works thus:

Van Mieghem caught it all: mothers with babies, children, bent old women, bearded men, as well as the people of the port: stevedores, sailors, ship captains, prostitutes, women who stitched bags for grain. Sometimes he froze his subjects in rapid sketches: a frightened old man clutching his umbrella; a scowling loner prowling the street, hands in pockets. A Kollwitz-like chalk drawing in black and red shows the gaunt head of a blind man as he gropes his way along a street of forbidding buildings. “Emigrants Waiting Near the River Scheldt,” a bleak view of two men and a child hanging out at a parapet over the river, depicts the trying vigil of those waiting for a ship.

For more on the Red Star Line:

Travelogue

Based on what we've learned, we can sketch out Ludwig Kurlandsky's early life as well as his trip to the U.S. He was born about 1875 in the region of Przasnitz in what was then a part of Russia very close to its border with Germany. Perhaps he was born in the town of Przasnitz itself. In either case, the ship's manifest says he could read and write, but presumably he was not very well educated, or his job would not have been merely that of a laborer.

At some point a brother, presumably older, emigrated to the U.S. and somehow found his way to St. Louis, which had a substantial Polish immigrant community, but not one as significant as New York City's, Chicago's or even Milwaukee's or Cleveland's. (Rosemary A. Chorzempa: Korzenie Polskie: Polish Roots, p. 25)

As is typical in the American immigrant story, a few years after his arrival, Ludwig's brother arranged for the passage of Ludwig himself, paying for his brother's fare not just across half the continental U.S., but possibly also across the Atlantic from Antwerp, and possibly to Antwerp itself, about 900 miles distant from Przasnitz. (Thanks to e-distance.com).

We don't know whether Ludwig arrived in Antwerp by land or by sea. In either case, he arrived at a time and a place that served as a major stepping-stone in the journey of (mostly poor) Europeans on their way to the U.S. However he came, this is probably what he saw as his ship departed for New York, for what emigrant wouldn't stand on deck to take his last look at the Old World? (Thanks to Wikimedia Commons photo of Antwerp circa 1900).

.jpg)

The top of the Pennland manifest reads "sailing from Antwerp, May 4th, 1901. Arriving at Port of 222, (date field left blank)." This tells us that the manifest was filled out shipboard well before the arrival date, perhaps at or just after the departure. The passenger record marks Ludwig's date of arrival as May 17—meaning a 13-day crossing.

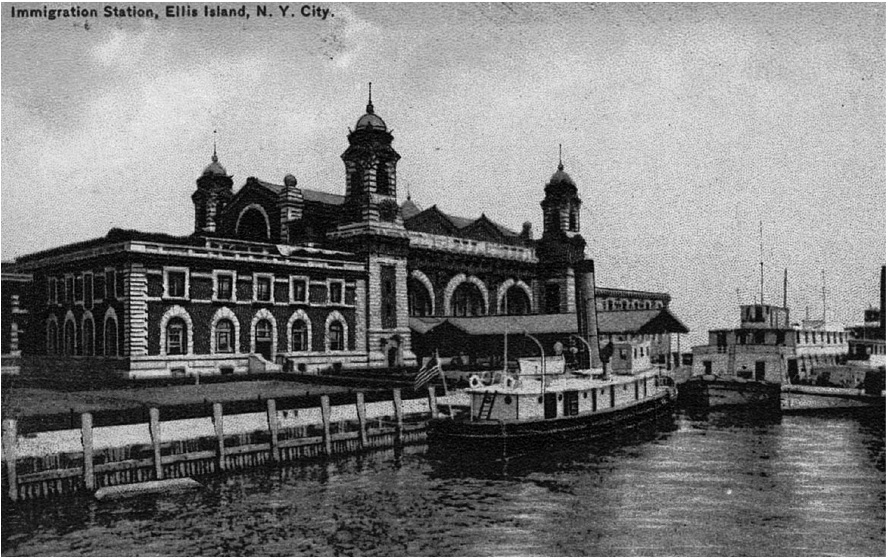

At the end of the fortnight's voyage, probably Ludwig stood on the deck with the other travelers as the ship entered New York Harbor with its Statue of Liberty. Less than a quarter mile away the ship would have pulled up to Ellis Island. (Credits to ancestry.com.)

Stepping off the boat, across the walkway and into the cavernous entrance of the government building, Ludwig was probably nervous. Surely he had heard stories of immigrants being turned away. But he had a lot going for him—his health, the physical strength of a 26-year-old man, a U.S. resident who was sponsoring him, and more than twice the $25 which the government estimated an newly-arriving immigrant should have. Sixty dollars wasn't a lot, but back then it meant he would probably have time enough to find work before he went hungry.

Here are a few of my own photos of the main part of the building, taken long after Ellis Island closed as an immigration center and, decades later, began its new life as a museum. Although probably much cleaner, not to mention less crowded, the architecture itself probably differs little from what Ludwig saw—the building opened on December 17, 1900, exactly five months before his arrival.

Recently I rewatched The Godfather, Part II. The film begins with a deep flashback which explains how Vito Corleone came to America in 1900. There is a poignant scene in which he, a child of ten or so, arrives at Ellis Island. I bring this up here not to plug the movie but to point out that the scene was, clearly, filmed at Ellis Island (you'll recognize the main lobby from my photographs above, and I recognize the dark hallways from my own visits there), and just as clearly, the filmmakers paid attention to historical detail when they planned and shot the scene. I provide a link to this snippet of the film below, but if the link goes bad you could easily find it by googling "Godfather Ellis Island scene." Of course, Ludwig was at least two decades older than the young Vito Corleone shown here, but if we ignore the child and focus on the background, maybe we can get a sense of what our Ludwig saw when he arrived in 1901.

Ellis Island scene from The Godfather, Part II

From New York, or perhaps Jersey City on the other side of the Hudson River, Ludwig no doubt took a train to St. Louis and probably arrived at Union Station, opened in 1894. (Photo thanks to Wikimedia Commons)

Wikipedia: St. Louis's Union Station describes Union Station as "the largest and busiest train station in the world in 1894." So take that, NYC.

Finally Ludwig could join his brother. Within just a few years he would meet and marry Sophia Wroblewski. See Sophia & Ludwig, the Early Years for the story of this Polish-American couple.

Notes

Polish Geography

(referenced in Przasnysz)

There may be a more detailed view of whether Przasnysz was part of Germany or of Russia in 1900 at Old maps of Lithuania. But if there is, I haven't found it yet.

Ludwig's Siblings

(referenced in Other Details)

Cousin Stan Piekarski has sent me a few emails, providing the information that Ludwig had two siblings, a brother named Ignatz and a sister named Helena. I can't make out the name of the brother mentioned in the manifest, above, but it doesn't seem to be "Ignatz." Yet another mystery that must be elucidated.