On this page I share what I've learned about the various occupations of my great-grandfather Ludwig Kurlandsky, also known as Louis R. Kurlandski, and the husband of my great-grandmother, Sophia M. Kurlandski, née Sophia Preis.

The family history has him as a cobbler--with a shop on Cass Avenue, it is said. He is also described as a tool-and-die maker. And Georgia Lee Kurlandski-Long has sent me a photocopy of a letter between her and her father, Frank. She asks him, "Did Grandpa work for the railroad, or what did he do?", and her father replied with the line "wagon maker machinist".

1910 and Before

As we've seen from the Ludwig Kurlandsky, Immigrant page, Great-Grandfather Ludwig entered this country as a "Laborer." It's reasonable to assume that this means that he was used to, and willing to engage in, any sort of hard physical labor asked of him.

By 1910, nine years after entering this country, Ludwig was employed as a blacksmith at a wagon factory. Here is how he replied to the questions asked of him in the census of that year.

| Trade | Workplace | Currently Employed | Weeks unemployed in 1909 | Own/Rent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blacksmith | Wagon factory | Yes | 0 | Rent |

It would be nice to learn he became a blacksmith after immigrating to the U.S. as a laborer in 1901. This is a gap in our knowledge that will perhaps never be filled.

However it came about, the career change appears to have paid off. Compare Ludwig's employment info to that of the other heads of household on the same census page: The 1910 Census record for Sophia and Ludwik Kurlanski. Another blacksmith, Ludwig and Sophia's neighbor Frank Klupp, had been unemployed 28 weeks in 1909. William Dawson, a boilermaker, had been unemployed 22 weeks; a third neighbor, John Preuse--a "laborer," as Ludwig had been when he entered the country--had been without work for 47 weeks the previous year.

Go down the list of the census data and you'll find many neighbors who were worse off than Ludwig in 1910. Still, when I learned that he was a blacksmith in a wagon factory, I couldn't help but see him as a worker in a doomed career. The Model T began production in 1908: in just a few years the horse-driven wagon would be an anachronism. How would he manage to continue supporting his family?

A Doomed Career

I began a little research on Ludwig and his "doomed career," and was quickly able to find a summary of the history of blacksmithing, with the following lines:

In a typical American town in 1900, one would expect to find livery stables, feed stores, wagon shops, blacksmith shops, horse corrals, horse traders, and horse trainers in about the same ratio that we now find auto dealers, repair shops, parts stores, driving instructors, and fueling stations. This shows how much the blacksmith was a part of the local economy. The change was quick and significant.

Introduced in the 1890's, it would not take long for America to begin its love affair with the automobile. The technology of the cotton gin came of age in the automobile assembly plant. More than anything else, motorized vehicles and farm equipment doomed the trade of blacksmith. (Blacksmithing History)

So we know that Ludwig would soon have to find a new trade.

The Wagon Factory

Forgive me. In this section I engage in pure conjecture, with little grounding in established fact... But what's the harm in a little fun?

Hoping to fill in our knowledge about Ludwig's progression from laborer to blacksmith, I did a little research on wagon factories in turn-of-the-century St. Louis.

In fact, there was a bustling wagon factory on the North Side not far from Ludwig and Sophia's home. It was called the Gestring Wagon Factory, and it was active from 1875 until 1935. The company was founded by a German immigrant named Casper Gestring and his partner Henry Becker in 1866, and within a decade they were doing well enough to build a new factory on the corner of North Broadway and Mound Street.

The new building had four stories, plus a black-smith shop in the basement, and employed 35 craftsmen. The company continued to manufacture hand-made farm wagons well into the 20th century, while their closest competitors shifted to the automobile. Finally, in 1935, the Gestring Wagon Company closed its doors, ending the age of the hand-made wagon. (Miller County Museum & Historical Society)

Years later the remains of the site were discovered, and soon they were "determined to be remarkably intact and historically significant, with the potential to provide unique information on the development of wagon and carriage manufacturing in St. Louis."

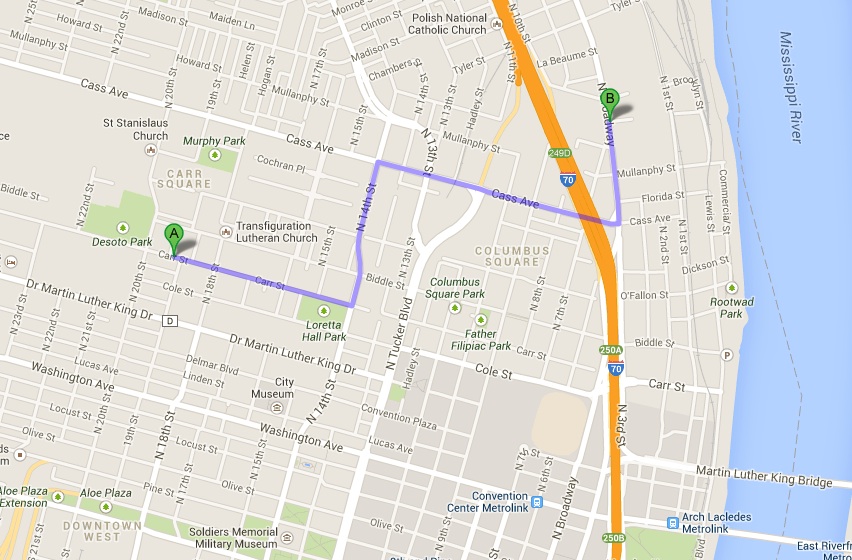

It seems plausible that Ludwig might have worked at Gestring. First of all, the census specifically states he worked in a wagon factory; his blacksmith neighbor Frank Klupp, mentioned above, is listed simply as working in a shop. Second, the company founder, being a German immigrant himself, is more likely to have been willing to hire a German-speaking Pole whose English was perhaps weak. (See discussion of this question on the 1910 Census in the Ethnicity Data section of the "Sophia & Ludwig, the Early Years" page.) Finally, the factory was very close to his home, as the map below shows.

Google Maps has the trip as being just 1.6 miles long. In bad weather he could have walked straight north to Cass Avenue and taken a streetcar heading east.

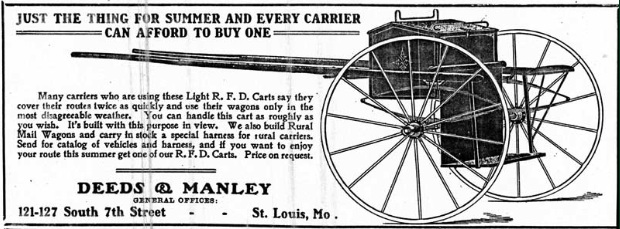

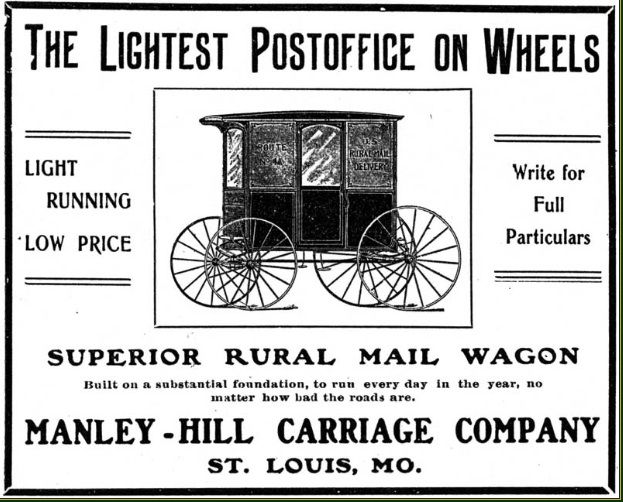

Another of Ludwig's possible employers might have been one of the several companies run by William C. Manley, which include the Manley-Hill Carriage Company, the John D. Manley Implement Company, and Deeds & Manley. As the advertisement below indicates, their address was 121-127 South Seventh Street. (Originally found at http://www.postalmuseum.si.edu/rfdmarketing/part4a.html, but the link is no longer valid)

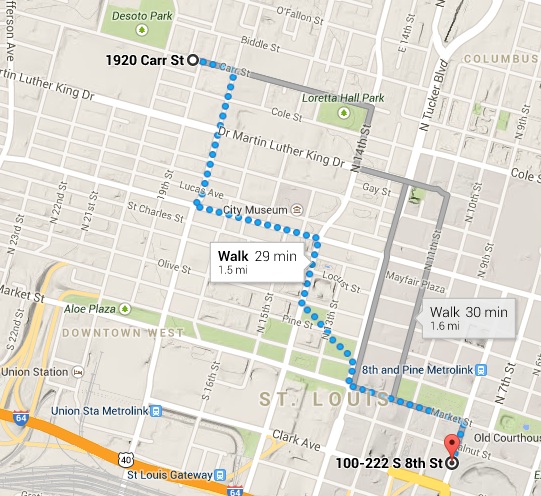

There no longer is such an address in St. Louis, but Google Maps has the distance from their home on Carr Street to 100 South Eighth Street as 1.5 miles.

Personally, despite the equal distance from his home, I think it less likely that Ludwig worked at one of the Manley companies. The census record specifically says he worked in a "wagon factory," not a "carriage company." There may have been little difference in the meaning of the two expressions, but I think it's significant that he chose one over the other. To be honest, I have mentioned the possibility that he might have worked for Manley largely because I find the old advertisements charming, and hope they will brighten up the web page.

One more note before we finish this section. It turns out that there is more history at the Gestring Broadway and Mound Street site than just blacksmithing--the "mound" in Mound Street refers to Indian mounds. On my first reading of the page linked to above, one sentence attracted my interest:

A significant portion of the property was mechanically excavated in an attempt to identify prehistoric, sub-mound features; no evidence of intact prehistoric deposits were found, although a handful of prehistoric artifacts were recovered from inside one of the cisterns.

A quick internet search brought me to a St. Louis Post-Dispatch page with the headline "A Look Back: Big Mound in St. Louis, legacy of a lost culture, leveled in 1869."

Although this is very interesting and I would like to further explore the topic myself, I admit that it is not really germane to our present discussion and so will leave it as an extra-credit project to anyone with a little extra time on their hands.

St. Louis Post-Dispatch article on the Big Mounds

After 1910

Here is a placeholder for any information on Ludwig/Louis's jobs after 1910. As we mentioned at the beginning of this page, he is said to also have been a cobbler and a tool-and-die maker.